The New World Energy Map

The article explores how 2020–21 disruptions reshaped global energy markets, driving volatility, high gas prices, and renewed geopolitical tensions while accelerating clean energy ambitions, net-zero strategies, and the redefinition of global energy security.

The new World Energy Map[1]

A conversation on clean energy, net-zero emissions and the energy trilemma

By Alessandro Nanotti

The unprecedented events occurred in 2020 and 2021 will have a long-lived impact on global energy for years to come:

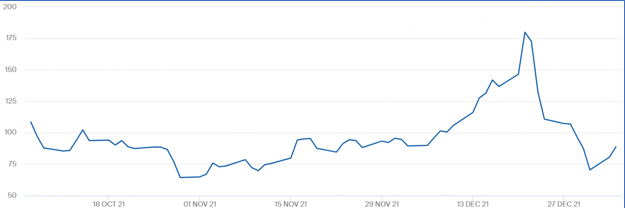

- Gas prices in Europe and the spot price for LNG in Asia reached sky-high prices: before 2021, the high point at the Title Transfer Facility (TTF) in the Netherlands was €35 per megawatt hour (MWh). Between August and December 2021, the closing price was above €35/MWh every day. For a brief moment, on December 21, prices topped €181/MWh (five times higher than the historical peak), with a direct spillover effect into electricity prices, further multiplied by rising CO2 emission credits costs reaching almost 100€/tonne;

- Oil prices reached levels seen last only in 2014 branching out to almost 100$/bbl allowing for a rebound of investments by IOCs;

- With oil prices expected to stay in the region of $70-$80/barrel and the cost of emission allowances going towards €100/tonne, electricity prices will continue to be high. Gas and electricity markets are strongly correlated, and rising gas prices have resulted, in turn, in more expensive electricity and gas bills for households, with worrying inflationary pressures for the medium and long term. Governments around the word will have to consider better and longer-term measures to support vulnerable households[2];

- Fossil fuels in general received a sustained battering, culminating in COP26, where for the first time they were directly referenced as contributors to global warming. This opens the sector to increasing attacks which will be reaching a climax at COP27 in Cairo in 2022;

- At the same time clean energy and renewables received a major boost at COP26 and this will be felt more strongly in 2022, led by the EU driving its green agenda, despite the current energy crisis.

What does this mean for the energy sector as we start the new year? Key factors that will shape 2022 are the state of the global economy, the EU’s green agenda, a decisive move towards clean energy combined with a sustained financial and political strain on the global oil and gas sector. These will inevitably impact developments, inter alia, in the East Med, Northern Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa which are the regions that still today struggle to reach energy security, affordability and access to all (as defined by the Sustainable Development Goal #7 established by the UN General Assembly in 2015).

Gas and LNG

The liquefied natural gas (LNG) market witnessed profound shifts in 2021. China finally emerged as the world’s largest importer, but that came with some costs: the price that China paid for LNG topped $18 per million British thermal units in November 2021, far above what the country paid for pipeline gas (with a price linked to oil), it also came with a growing dependence on Australia and the United States—a fact that strategists in Beijing are unlikely to welcome. The United States narrowed the gap with Australia and Qatar and is due to become the world’s largest exporter in 2022. LNG flows into South America spiked, driven by Brazil and Argentina droughts, while Mexico’s imports declined to almost zero as most gas is now imported from the US via pipeline and domestic production has risen. Egypt’s exports reached a 10-year high (driven by the high LNG prices, but might fall back if prices drop again), exporting almost 7 million tons of LNG: its exports went mostly to Asia, especially China, India, and Pakistan, but Turkey was the second-largest recipient of Egyptian LNG, which, given the constant complaints from Turkey that it is being shut out of the gas game in the eastern Mediterranean and the strained relations between the two Countries, is once more evidence that in the geopolitics of energy the security and affordability of supply count more than momentarily political talk. On the other hand, Jordan effectively ceased imports (all needs now satisfied through pipeline imports from Egypt and Israel, again a need for a new geopolitical energy map). India’s imported volumes declined (over concerns of high energy costs which forced authorities to switch back to coal, evidence of the country’s high price sensitivity), as did Europe’s. All these changes are a reminder that this market remains incredibly dynamic and fluid and that our mental maps of this system need to keep adjusting year after year.

Other countries faced serious supply troubles: LNG exports fell 90 percent in Norway, 35 percent in Peru, 32 percent in Trinidad, and 18 percent in Nigeria. Combined, those losses amounted to 11 million tons—enough to satisfy the import needs of a country like the United Kingdom.

In 2021, South America (because of droughts) imported a lot of LNG during the (Northern Hemisphere) summer, which left less LNG for Europe to import to refill storage. In fact, Europe was able to secure additional LNG in December only once the needs of South America subsided and Asian buyers decided to use reserves instead of increasing stocks for this winter, at that point prices consequently came down.

European Security of supply vs the new green deal

Europe is at the centre of an economic and geopolitical storm. Gas prices in Europe reached unprecedented levels in Q4 2021. Since last September, natural gas prices gradually increased, reaching a record value of 180 euros per Megawatt/hour (MWh) on December 21st. The December figures, when compared with the 20 euros per Mwh in mid-June, constitute a growth of 900%. In the second half of December, however, several dozen American LNG vessels were redirected from Asia to Europe, driven by rising prices. Immediately after the announcement, gas prices fell to 70 euros per MWh recorded on December 31st. Given the considerable increase in prices, Europe is in fact attracting new supplies, also considering the fact that the main Asian buyers have decided, for this winter, to use reserves instead of increasing stocks.

However, the price reduction turned out to be only temporary: on January 4, in fact, the price of gas almost reached 100 euros per MWh, after the Yamal-Europa pipeline – which normally transports gas from Siberia to Europe – transported gas from Germany to Poland for the fifteenth consecutive day, with the aim of meeting the latter's gas demand. Moreover, although seaborne LNG flows increased in Europe at the end of last year, these could fall again when prices for LNG in Asia return above European spot prices.

Dutch natural gas (FTT) prices, in euro per Mwh (Source: ICE)

This ample volatility in prices raise profound questions about how the gas market operates in Europe, about the role and responsibilities of supplier companies like Gazprom, and about the need to provide a better structure for managing the big swing in gas demand between summer and winter. Europe needs a new effort to strengthen the institutions meant to provide gas security, and it cannot let the imperative of the energy transition act as an excuse to delay this work.

These prices raise major questions about the functioning of the European gas market (and the spot market for LNG). The fundamentals did not justify such prices. The market was tight, of course, but not that tight. What drove prices up was a fear that Europe might run out of gas in February or March. It was anxiety, not an actual shortage, that drove prices so high. That’s why a modest amount of LNG going into Europe in December and January crashed prices. Could such a vicious cycle be tempered, especially since high prices did little to attract gas supplies (who wants to buy gas at the top and be left holding excess supply when prices crash)? This is a serious question for policymakers to grapple with.

Russia’s role in this crisis also deserves further scrutiny. At a minimum, it seems like Gazprom’s failure to fill its storage facilities in Europe was a major driver of the perceived inadequacy of European reserves for the winter[3]. Do companies have any obligations to use the storage capacity they have reserved, and could that capacity have been released to other parties? Should Europe impose the same responsibilities to external suppliers like Gazprom as it does to importers? Could this be a new avenue through which Gazprom exercises market power, even if its behavior in 2021 might be better explained by the need to refill storage in Russia after the cold winter of 2021? All these are important questions for Europe to consider.

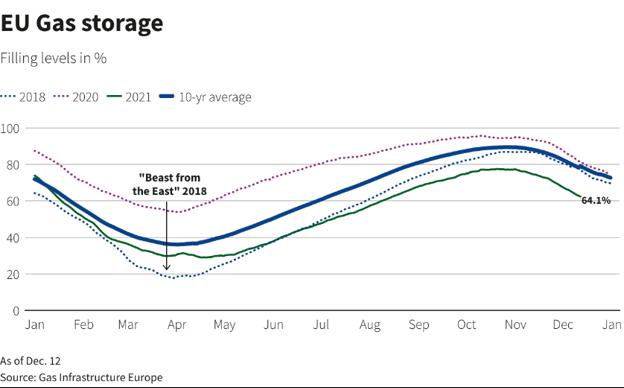

More broadly, these prices exposed a deeper problem for Europe: seasonal balancing and security/diversification of supply. In the past, Europe has relied on a mix of domestic production, storage, and pipeline imports to meet the huge seasonal swing in gas demand. With gas production declining, the continent is far more reliant on storage and imports, including LNG. This is a problem given the lack of sufficient storage to compensate for these imbalances in the gas market (the fill rate in September 2021 was just 77%, compared to 95% in 2020) and the reliance on spot LNG that has a high volatility. LNG is not very seasonal because it makes sense to produce at peak capacity year-round, and Asia absorbs the market’s seasonal capacity.

As for security of supply, following the second energy crisis between Russia and Ukraine in 2009, the EU launched a series of reforms aimed at reducing its energy dependence on a single supplier. In 2010, the new EU Gas Supply Regulation introduced new standards, a solidarity mechanism to be activated in the event of an emergency, and the requirement – for each Member State – to rely on three different natural gas suppliers. In 2014, the adoption of the European Energy Security Strategy accelerated the creation of international connections between Member States, to create a truly integrated energy market. The transition to a single market, the diversification of supplies and the increase in strategic reserves in European countries have contributed over the years to reducing the risks deriving from external shocks, but, as recent events highlighted, has not been enough.

This leaves Europe in a difficult spot, exacerbated by the push towards lower carbon emitting energy sources and the move away from fossil-fuels, which still today represent the majority of its energy sources[4]. Will the EU be able to come out of its current energy crisis by spring (thanks to US LNG flowing in larger volumes towards Europe) and see prices gradually return to more-or-less normal levels by summer?

Given the new package of gas legislation announced on December 15, where the EU is determined to steer Europe away from unabated natural gas towards more sustainable energy sources, like renewable and low-carbon hydrogen, starting in 2022, this matter cannot be seen in isolation, but requires a profound revision of the energy strategy of the EU. Europe needs a more permanent fix to this problem. No matter how quickly the energy transition takes place, this seasonal challenge will persist. Europe needs better solutions and the Fit-for-55 package proposed by the European Commission (EC), targeting to reduce emissions by 55 per cent by 2030 and to net-zero by 2050, does not seem to include a solution for Europe’s energy security issue. Some relief may come from the new taxonomy for sustainable investments recently proposed by the EC and currently being debated[5] whereby efficient unabated gas-fired power plants (provided that the overall emissions are kept under a certain – very low – threshold) and nuclear plants could be classified as transitional investments and considered as green energy sources[6].

Even though the EU is about to include natural gas in its taxonomy, this is a temporary reprieve. The use of unabated natural gas in the EU is set to decline, even if the EU classifies investments in gas-fired plants as transitional investments. It still aims to reduce consumption of unabated natural gas by 25 per cent by 2030 and to eliminate it altogether by 2050. That’s why it has now banned long-term gas supply contracts beyond 2049, which in an era of greater volatility and uncertainty for gas supplies, as well as dependance on Russian gas (which is sourced on long-term contracts mostly coming to expire before 2049) might not have been the best choice.

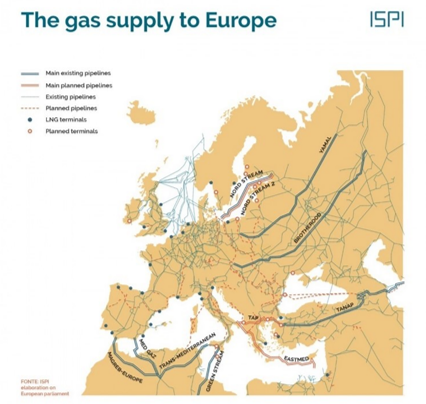

Notwithstanding, or rather, in light of the above, all eyes will be on the fate of the delayed final certification of Nord Stream 2. It is already loaded with gas and ready to operate. To a certain extent this may be linked to the outcome of the Russia-NATO talks that will start in early-2022. My expectation is that the pipeline will start operating Q3 2022.

All these imbalances at the regional level have resulted in an unprecedented energy crisis also due to a structural element: the insufficient supply of natural gas. Since 2014, in fact, investments in the research and development of hydrocarbon deposits in Europe have collapsed. At a time when investment had begun to recover after the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, a momentous event revolutionized energy markets: the Paris Accords, which marked the end of the fossil era, as we knew it since then. On the one hand, oil companies have drastically reduced investments and their time horizon, concentrating the few resources available in operations that could guarantee the greatest profits in a few years (mostly offshore and in frontier plays). The European Investment Bank (EIB) itself has completely embraced the energy transition and is progressively excluding fossil fuel investments from its portfolio, thus becoming the de facto European Climate Bank.

At the same time, however, investments in renewable energy have not been sufficient to meet the growing demand globally, especially in Europe. In addition, energy prices in Europe are based on the marginal price mechanism: the hourly cost of energy is decided by the source which, at the present time, is indispensable for the grid. More simply, renewable sources set the price of energy only when they are so abundant that they saturate the market. And this, typically, happens only in times of low energy demand, thus leading to equally low prices. As a result, the main role in price mechanisms is still played by fossil fuels, and in particular by natural gas (which is the fuel of last resort once coal, nuclear and renewables have been all saturated).

Global economy and the energy transition

The priority in 2022 will be to stop the pandemic and ensure that the recovery in the global economy continues, but this faces many risks. These include inability to control Omicron, or the next variant, leading to more lockdowns, inflation, and rising food prices, escalation of the Russia-Nato and China-Taiwan confrontations, a weakened Biden, failure of the Iran nuclear talks leading to a crisis, a hotter summer and even more extreme climatic events, another oil crisis, political turmoil in Europe or Central Asia, to name but a few risks to global economic recovery.

The last two European Council summits have shown a divided Europe on many key issues. With Angela Merkel out of the way, elections in France in April, a fragile coalition in Italy, political instability in the UK and the possibility of even further deterioration in EU-UK relations could trigger political turmoil in Europe with far-reaching consequences.

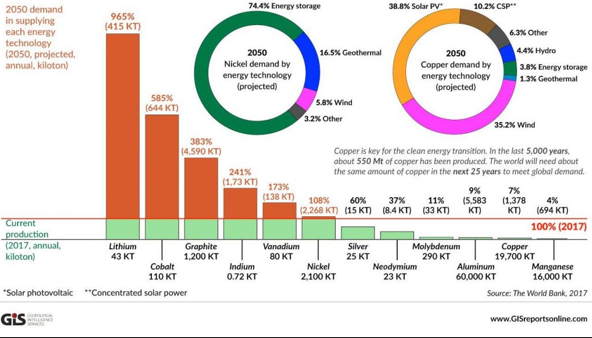

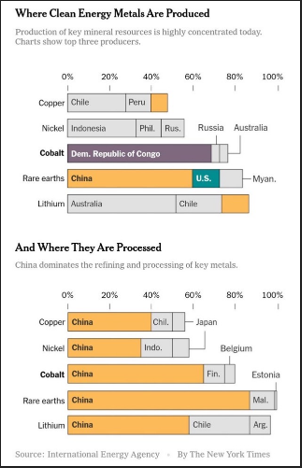

COP26’s ambitions were compromised by partisan interests and the pursuit of local, national and regional agendas will no doubt continue to have an impact on the energy transition in 2022, even in the EU (where the reality of high energy prices need to be tackled in priority, potentially diverting some of the money set aside for the green deal) and in the US (where President Biden’s Build Back Better Act was criticised even by members of his own party). More widely, ongoing tensions between China and the US do not bode well for industries such as renewable energy, which are highly dependent on Chinese goods and its processing capabilities of all the mineral components for the renewable industry – are we de facto putting ourselves in the hands of China to pursue the energy transition objectives of the Paris Accords and the EU Green Deal?

China, the world’s largest producer of solar, wind and hydro energy – as well as coal – has a shot at global hegemony as it tries to dominate the green energy space, directly and indirectly (pushing, for example, for EVs rather than ICEs which are steadily in the hands of European and American carmakers). The World Bank wrote in a 2017 report, “the most notable finding is the global dominance China enjoys on metals – both base and rare earth – required to supply technologies in a carbon-constrained future”.

Demand for metals and minerals in a 2-degree Celsius rise scenario

The alternative energy megatrend might lead to unforeseen geopolitical divides based on the new global resource map, ultimately creating tensions over energy-related spaces and geography. But even before the dominance of green energy is fully established and the world finally turns the page on the fossil fuels era, the dynamics at the early stages of the process will also have interesting geopolitical implications.

In Europe, meanwhile, Russia’s pressure over Ukraine will hopefully not lead to outright conflict but could easily result in European sanctions affecting energy markets. The Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline has already been singled out as a strategic asset amid escalating tensions[7].

In the end, for the energy transition to accelerate, fossil fuels need to become more expensive to encourage substitution. But if a cheaper, greener, alternative is not readily available (for example, wind generation capacity in Europe is still too low), nations will resort to other means to avoid a major energy meltdown.

There is, though, hope that things will go right in 2022 and global economic recovery will continue, with economic growth even accelerating.

IOCs turning to new investments

International oil and gas companies (IOCs) are under intense pressure from their shareholders, activists, governments and the financial sector to decarbonise make their activities emitting less GHG (including most importantly methane). Almost all of them acknowledge that their future is tied to energy transition. Even ExxonMobil and Chevron are committing more and more of their reduced capital spending to clean energy projects and low-carbon fuels[8].

The emphasis now is on frugality, less spending, consolidation, greater margins, share buy-backs and returns to shareholders. The old days of portfolio expansion, increasing investments in new oil and gas and risk-taking are long gone. The cost of capital has also more than doubled in comparison to ten years ago, limiting the ability of IOCs to invest in long-term projects.

As the world shifts irrevocably and inexorably towards clean energy and net-zero emissions, the oil and gas industry is finding itself under siege on multiple fronts. This pressure will only increase in 2022. If Omicron gets out of control it could be even more difficult for the IOCs.

At the same time, given the increase in oil prices, investments in exploration and development are coming back: global oil and gas investments are expected to expand by $26 billion this year as the industry continues its protracted recovery from the worst of the pandemic and the hurdles imposed by the Omicron variant. An analysis by Rystad Energy projects overall oil and gas investments will rise 4% to $628 billion this year from $602 billion in 2021.

A significant factor behind the increase is a 14% increase in upstream gas and LNG investments. These segments will be the fastest-growing this year, with a jump in investments from $131 billion in 2021 to around $149 billion in 2022. Although this falls short of pre-pandemic totals, investments in the sector are expected to surpass 2019 levels of $168 billion in just two years, reaching $171 billion in 2024.

Upstream oil investments are projected to rise from $287 billion in 2021 to $307 billion this year, a 7% increase, while midstream and downstream investments will fall by 6.7% to $172 billion this year.

This year’s investment growth is very much pre-programmed by the $150 billion worth of greenfield LNG projects sanctioned in 2021, up from $80 billion in 2020. Sanctioning activity in 2022 is likely to closely match 2021 levels, with a similar amount of project spending to be unleashed over the short to medium term.

Sanctioning activity is set to rebound in North America, with over $40 billion worth of projects due for sanctioning in 2022. Six LNG projects are expected to receive the green light, five in the United States and one in Canada. Offshore projects will also provide ample opportunities for contractors as TotalEnergies’ North Platte project enters the final stage of its tender process and LLOG Exploration’s Leon and Chevron’s Ballymore developments in the US Gulf of Mexico look to proceed to the development phase in 2022. For Africa, however, 2022 is expected to be another quiet year with expected sanctioned projects worth a comparatively small $5 billion.

The number of sanctioned offshore projects is expected to rise year-over-year but will remain little changed when measured by capital commitments. An outstanding concern for 2022 is execution challenges related to the pandemic and increased inflationary costs for steel and other input factors. These are likely to make operators mildly cautious regarding significant capital commitments. In addition, major offshore operators are being challenged on their portfolio strategy as the energy transition unfolds, with many exploration and production companies already directing investment budgets to low-carbon energy sources.

Outlook for the East Med

The only country in the region where hydrocarbon activities will carry on as normal in 2022 is Egypt. Israel has already announced a halt on offshore exploration at least until the end of 2022 so it can prioritise the development of renewable energy. To a certain extent lack of state support has brought offshore exploration to a standstill also in Greece.

Priority is given to the renewable energy sector, with licences awarded to renewables projects with a total capacity of 95GW and to 14.3MW storage projects. It has a target to increase the renewables share of electricity by 61 per cent by 2030. With IOCs under immense pressure, Lebanon will also not be able to progress offshore exploration, but its electricity sector should receive support from Jordan and natural gas from Egypt in 2022.

But the rogue in the region will continue to be Turkey. With its economy in tatters, collapse of the lira and out-of-control inflation usher in unpredictability and danger. In addition, with presidential elections expected in 2023, and Erdogan’s chances of re-election slipping, anything could be expected, including the creation of a crisis to bolster his position. 2022 should be a year of vigilance in the East Med.

Cyprus has re-commenced offshore exploration with drilling already in progress in Block 10. It has also awarded block 5 to ExxonMobil and QatarEnergy. Appraisal drilling should be completed by February, with results expected to be closer to the upper limit of the range of 5-8trillion cubic feet gas at the Glafkos discovery announced in 2019.

But other than that, a long period of inactivity is likely to follow.

Europe’s decisive moves towards clean energy and determination to stop use of unabated natural gas will bring an end to the long saga of the EastMed gas pipeline in 2022, which in all honesty never stood a chance in any case.

The much-heralded import of LNG will not materialise in 2022, and probably not before 2024 at the earliest. As a result, it will not bring the benefits it has been claimed it will (but will bring the penalties the EU charges to countries not meeting its emission targets).

Alessandro Nanotti is an Energy and Geopolitics expert and an independent consultant with 15+ years of experience in the O&G, LNG and Power sectors

[1] I owe to Daniel Yergin and his most recent book (“The New Map”), as well as the previous two (“The Prize” and “The Quest”), much of my passion and interest for the energy transition, the geopolitics of energy, how the politics of energy impact international relations and the key drivers of the energy markets.

[2] German consumer power bills are rising by over 60 percent, while in Italy they will increase by over 40 percent and in Poland by 54 percent.

[3] As stated by the IEA itself, the increase in gas prices in Europe is largely explained by the reduction in Russian gas flows. And the motivations, again according to the IEA, seem to belong to the geopolitical dimension: the Moscow government would be using the gas lever as an instrument of political pressure towards the EU with reference to the Ukrainian situation and the North Stream 2 clearance.

[4] The EU only produces 39% of its energy needs, importing the remaining 61%. The energy mix consists of oil (36%), natural gas (22%), renewable energy (15%) and nuclear (13%). Specifically, the Union is heavily dependent on Russia for natural gas, with Moscow accounting for 41% of gas imports.

[5] On the face of it, whether unabated gas-fired plants will be defined as 'transitional investments' in the EU taxonomy could be a moment of truth for the global gas industry. Financial and non-financial investors will be able to increase their corporate 'green scoring' by investing in gas, including outside Europe. Other countries developing similar taxonomies will be emboldened to include gas too, particularly in Asian markets where coal still dominates, as South Korea has recently proposed.

But the EU recognition of gas power plants as a transitional investment is no panacea for the gas industry. Gas prices will need to come down to accommodate increased investments in gas use. And the proposed CO2 emission cap of 270g/KWh, alongside the commitment to use at least 30% of renewable or low carbon gas by 2026 and 100% by 2035, means that the use of conventional natural gas would need to reduce over time if a gas fired power plant has to be classified as 'transitional'.

[6] The European Commission presented to the 27 member states of the EU bloc at the end of last year a draft green (sustainable) labelling of nuclear and gas power plants to facilitate the financing of facilities that contribute in the fight against climate change.

The document establishes the criteria to classify investments in nuclear or gas power plants for electricity production as “sustainable”, with the aim of directing “green finance” towards activities that contribute to the reduction of greenhouse gases.

[7] Nord Stream II is a replica of Nord Stream I which, even before its inception, was a politically divisive pipeline. These pipelines are seen as increasing Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, thereby weakening the continent’s energy security especially when Russia is perceived as manipulating its gas supplies to Europe for political gains. However, Nord Stream II will not only increase the continent’s reliance on Russia (and make Russian gas cheaper and more competitive with respect to US LNG), it will also enable Russia to significantly reduce its dependence on Ukraine which would subsequently suffer economically from the loss of transit fees. In fact, Nord Stream 2 would allow Russia to achieve its ultimate aim of bypassing Ukraine, the largest gas transit country in the world.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow has been gradually reducing its reliance on Ukraine to export Russian gas to its most lucrative market – Europe. In 1991, 95 percent of its gas exports to Europe were shipped via Ukraine; today, it is 42 percent. Russia has built a web of pipelines to diversify its gas export routes, starting with the Yamal pipeline to Poland and Germany via Belarus in the 1990s; then Blue Stream under the Black Sea to Turkey, and Nord Stream 1 under the Baltic Sea to Germany. With the completion of Nord Stream 2, Ukraine’s role in transporting Russian gas would be reduced to 13 percent of Russia’s exports to Europe. If Turk Stream 3 and 4 are built as well, supplying gas to Southern Europe via Turkey, Ukraine’s transit business will vanish.

Bypassing Ukraine presents challenges not only for Ukraine but for Europe and other Western allies, at least in the short term. The Ukrainian economy is still precarious. Transit revenues averaged 3 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) over the last 10 years – a substantial source of revenue to a government strapped for cash. The loss of transit revenue will also affect other transit countries including Poland, Slovakia, and to a lesser extent the Czech Republic. The new pipeline will allow the Kremlin to contest Ukraine’s transit fee policy.

Furthermore, the EU would be more exposed to Russia as it would not only rely on a single country for the lion’s share of its gas imports but also on Nord Stream as a single transport route. Nord Stream 2 is a replica of Nord Stream 1; it follows exactly the same pathway under the Baltic Sea and lands in the same location in Germany. Both projects have the same import capacity of 55 bcm per year each, 110 bcm per year combined (a fifth of European annual demand which is around 550bcm). If Nord Stream 2 becomes fully operational, around 110 bcm out of 170 bcm of Russian gas deliveries to Europe (65 percent of total deliveries from Russia) will travel through a single transport corridor.

[8] CCS, clean hydrogen and floating offshore wind are all low-carbon technologies that could have a mass commercialisation in the near future and where the oil and gas sector could achieve leadership and massive scale. Companies in the industry have already been positioning themselves in these nascent technology niches. In 2022 we can expect to see further moves to capture market share and grow capabilities.

ExxonMobil, to take one example, last month announced a memorandum of understanding with SGN and Green Investment Group to explore the development of a CCS and hydrogen cluster in Southampton, UK. BP, meanwhile, announced the first engineering contracts for the Northern Endurance Partnership carbon capture project in Teesside, Northeast England - First production at the HyGreen plant is slated for 2025, with a final investment decision in 2023.

This process could help determine which technology niches offer the highest returns and are the best fit for oil and gas companies, although the relative weighting of investments in low-carbon technology is likely to be driven mostly by corporate and regional market characteristics.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!